| Also read this in our Vichaar Repository | Summary posts available on Instagram |

Preface

The Kisan Morcha has begun again. After the first time, an essay was produced called “The Kisaan Morcha was NOT a Victory” which was a retrospective analysis from an Azadist perspective as to the factors that caused the Indian agricultural industry to be so broken in the first place, and a series of measures that should be demanded to improve the situation.

The fact that the Morcha has had to start again proves the labelling of that essay as appropriate. It wasn’t a victory, and now reading through some of the demands put forth this time, it doesn’t seem like this one will be either. Until there is a fundamental restructure and reprioritisation of the Indian system, the people of India (and the world) will continue to suffer.

Therefore, that essay is still just as (if not more) relevant now for those of you who wish to understand what is truly going on and potential ways to solve it.

You can also read it you can read it in our Coda-based Vichaar Repository or view summaries/excerpts of select sections by following our Instagram page. This Substack article contains all the sections from that original essay, however, the references and endnotes are available only in Coda. You can click the numbered links to be taken to them directly. If you are viewing this via the mobile app or website, you can also listen to this being read to you by clicking the icon above.

The Vichaar Repository for this hosts the below essay as well as potential further Vichaars that may be added as this Morcha develops. If you would like to contribute to this repository, send us an email at contact@azadism.co.uk.

Primer on Market Economics

Before delving into the economics of the current Indian agriculture industry, let’s first establish how a market system should work in theory.

In a market economy, many buyers and sellers interact through voluntary transactions to achieve a mutually beneficial outcome. On one side you have the farmers (producers) who grow the crops and make them available for purchase. Customers, be they businesses or individual consumers, seek to buy these crops off the farmers. Both sides are seeking to have their own interests met.

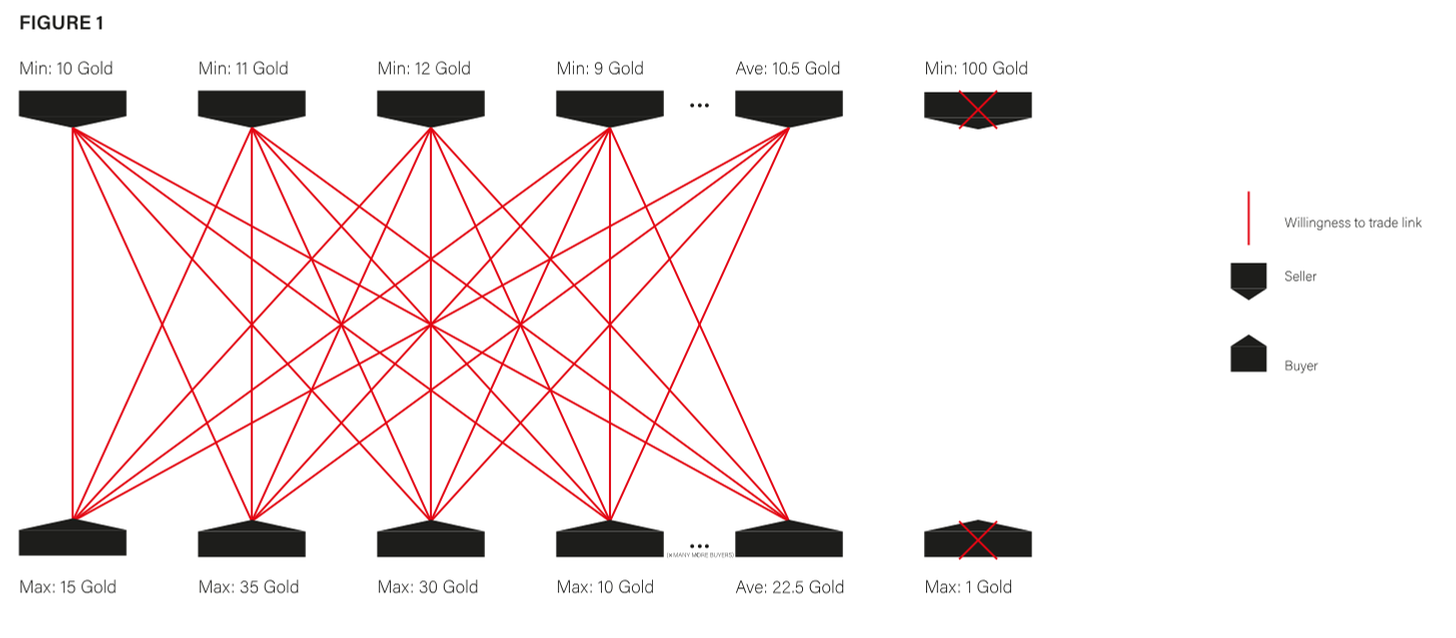

Now, each farmer has a minimum price in their heads that they are willing to sell for. They would not like to give away their produce at a price lower than this, but would be happy to sell at any amount above this. Simultaneously, each consumer has a maximum price they are not willing to pay more than in exchange for these goods. This conflict of interest allows for a natural market price to develop where most producers are willing to sell at a price most customers are willing to pay for.

As illustrated in Figure 1, when there are many buyers and many sellers, no one farmer can charge an extraordinarily above market rate (since buyers will go to another farmer), and no one buyer can put in too low of a bid (since the farmers can sell to someone else). There is ample competition and therefore many choices and alternatives available. Each buyer and seller will negotiate an agreement that is unique and mutually beneficial to them, however, overall the price of the same good would tend towards a natural, average level. What determines the maximum amounts each consumer in the market is willing to pay is entirely subjective and may be a result of a multitude of factors. Similarly, the farmer must also consider the costs involved to grow their crops and profit they need to make to fund their own needs and wants.

Since not everyone has perfect information, or is perfectly rational, there may be better or worse trades, but they all fall under a general average price. Hence, if everyone knew about and had access to the farmer willing to sell at 9 Gold pieces, they would all go to him. However, even then his supply is limited, and so the buyers would then tend to go to the next best, and then the next best after that etc.

This all ensures the best interests of the most possible people are met as each buyer and seller are able to trade at a price they both agree on [1].

Theory Vs Reality

So what is the issue in India? Why doesn’t this currently work? The problem arises when there is not enough competition.

As of right now, the buyer’s market is largely dominated by two groups. The first is the central government through the state approved ‘mandis’. A system originally set up by the British [2], these are yards overseen by the government who purchase state approved crops at fixed rates, regardless whether there is an actual consumer demand for them or not. Hence warehouses fill up with crops that didn’t go on to sell to the rest of population (surpluses). The state can not just export them and get rid of the surpluses on the global market either. Price control polices (which we will discuss next) make crops like wheat and rice cost 20-30% more, making Indian crops uncompetitive in international markets [3].

The second group is the state-backed ‘monopolies’ and corporations. The state-backed aspect is very important here, since through their links with the government they are able to establish barriers to entry into the industry, thereby gaining an unfair advantage over their competition. Through a practice known as ‘corporate political activity’, and lobbying in particular, they effectively bribe the government into securing their market shares and inhibit the ability for others and small businesses especially to compete with them.

Alongside this, the top offenders of such practices, namely Ambani and Adani, have used the governments influence over the economy to establish monopolies over multiple industries in India. This all further solidifies their position as conglomerates, thanks to the support they are able to negotiate with the government.

To deny this link is foolish. Whilst data on the amount each of the above mentioned “business”-“men” (both these words are questionable) spends on lobbying is not as easily available in India, Ambani’s company Reliance’s lobbying expenditure in the US can be accessed online [4]. If they lobby foreign governments we can be sure they do so domestically as well. From Modi flying around in Adani’s private jets to other special privileges, the corporate pandering towards the state is clear to see [5].

Let’s visualise all this in Figure 2:

Here the buyers are restricted to just two participants for simplicity. Since the farmers all need to sell their produce, the buyers now have a far stronger negotiating position. Instead of the buyers having to conform to the average market price established in a competitive system, they now have a ‘price-setting’ power. Now the farmers have only two options: either don’t sell at all and receive nothing, or sell at whatever price they can get so that they at least get something. This was the valid fear amongst many farmers by ‘privatising’ the system through getting rid of government mandis.

So, to answer why is it not working? In short, because the government is involved. The state has distorted the otherwise natural market forces of supply and demand in this sector by restricting the level of competition to help the big players. The whole state apparatus is being used as a tool to consolidate power and wealth into the hands of a few.

MSP is a State Supplied Drug

... and the government is the drug dealer.

Through the government mandi system, the state is also participant in the market. The state being one of the sole purchasers of farmers’ crops (and obviously the law setters), they have immense price-setting power also. However, the incentives are slightly different for the state since they need to ensure their own political reputations and secure vote blocks. Due to this, and also having all their costs paid for through taxpayer’s money, there is little incentive to keep costs low. As a result, the state’s maximum price, unlike businesses, is not set at the lowest possible. They instead aim to set the prices manually to a level where they balance an adequate price for farmers and consumers.

However, these sorts of price control policies are almost universally agreed by economists to be an ineffective strategy to set prices and leads to faulty outcomes [1]. But to see why, lets briefly go over how prices are naturally set through the laws of supply and demand.

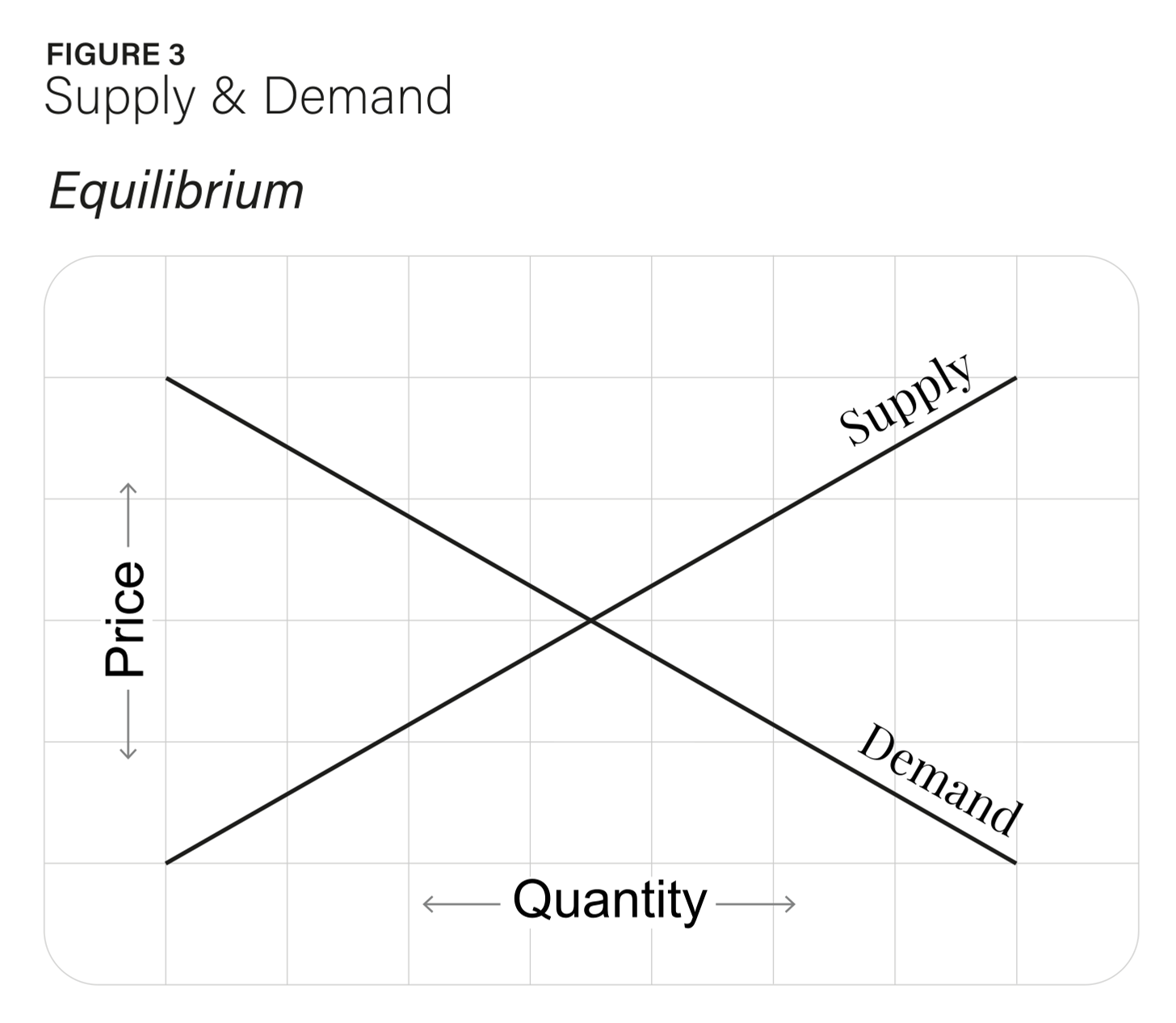

The law of supply states that at higher prices, sellers will supply more. The law of demand states at higher prices, buyers will demand less. These laws can be represented graphically in Figure 3, with a downward sloping demand curve and an upward sloping supply curve. The point at which these two curves meet is known as the equilibrium, natural market price.

This is the point where the most suppliers and consumers are willing trade with each other. Different factors can affect this equilibrium, causing either movements along or shifts of these curves entirely. For example, a meteor hits a region, temporarily restricting the supply of wheat. With this, the price would have to go up as the demand remains the same for a now rarer good. This higher price would then give an incentive for new entrants to come into the market and supply that good in order to secure a higher income. As this happens, the supply rises back to the normal level as these new suppliers grow more wheat, re-establish the logistics and compete with each other. Therefore, this brings the price back to the natural rate as the supply gets closer to the consumer’s demand.

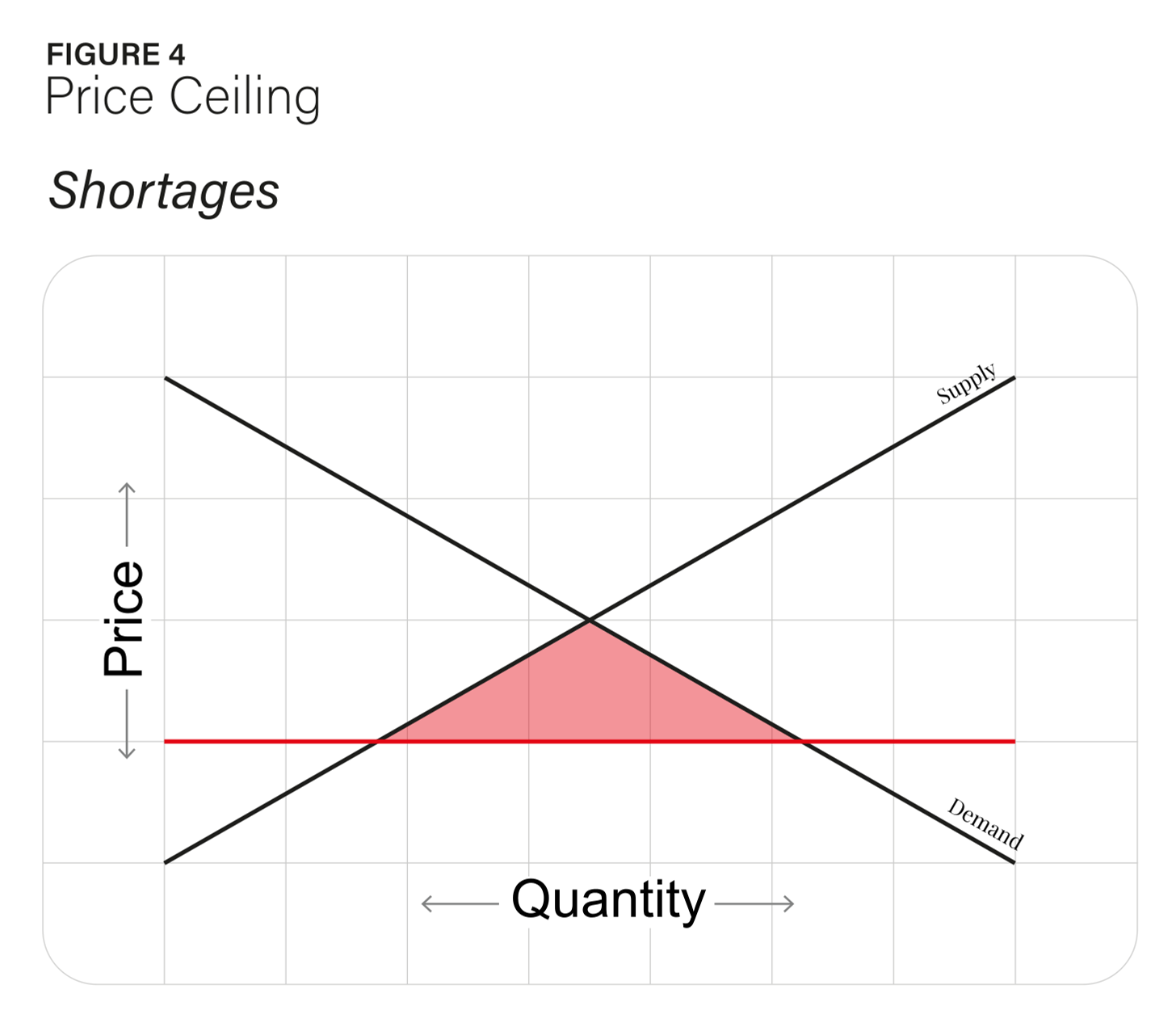

So what happens when government sets the price rather than the market? Figure 4 shows the effect of setting a price ceiling (i.e a maximum price suppliers cannot sell above) that is below what the market price would have been. As a result, the incentive to produce so much diminishes as there is no profit in it for the supplier [2]. This then leads to shortages as the quantity supplied does not meet the quantity demanded by consumers.

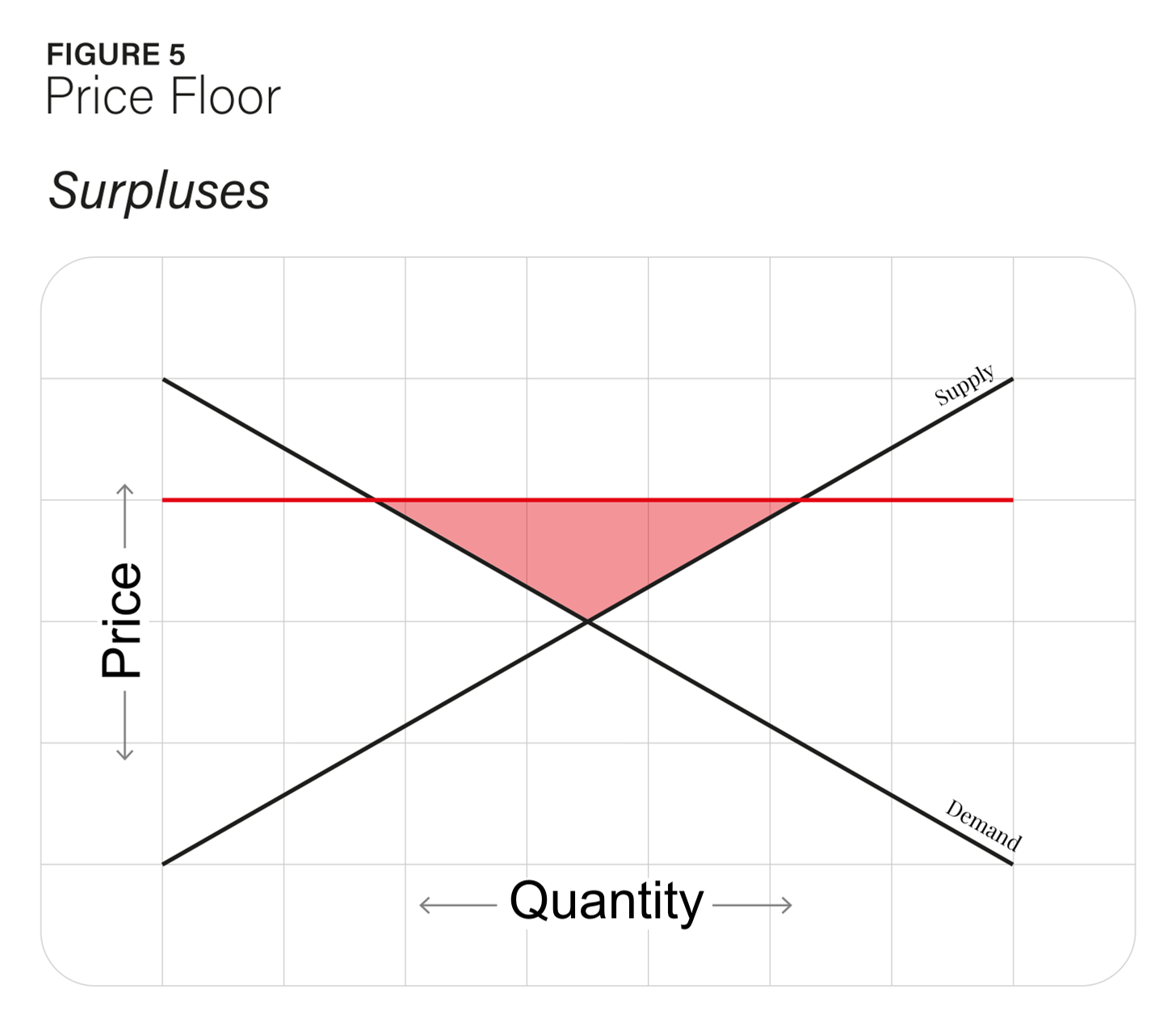

Figure 5 shows what is currently being employed by the government in India using the minimum “support” price (MSP). By setting a price floor (a minimum price a good must sell for) that is above the natural market price through having the government guaranteeing purchases, then the incentive is just to produce as much as possible regardless of actual consumer demand.

Initially, this may not seem like such a big issue since it would just result in surpluses, and you may think it’s better to have too much than too less. However, consider the reality here. The ecological situation in Punjab is a disaster. By having the government guarantee income through ecologically unsustainable crops, the farmers will just keep growing them. For example, growing rice is a very water intensive process that has never really been in the traditional farming culture in the region [3]. However, due to the incentives established through government price controls, rice cultivation is widespread and consequently the water table in Punjab is drying up with estimates suggesting that the land will be classed as a dessert by 2040 [4].

Despite efforts to educate farmers about the environmental issues [5], the MSP and mandi system have made them reliant on the government for their income. The central government has developed an insane amount of power over the financial security of the farmers. Whilst initially it may have sounded great politically telling farmers that the government will provide a safety net through always guaranteeing them income for what they grow [6], the unforeseen consequences of this are being realised today. Now farmers are extremely reliant on the MSP and fear the risks of its removal. We can’t really blame them for this either at this point, since by removing it now would be disastrous without an alternative safety net in place. The whole situation is akin to a heroin dealer giving you the first dose for free, knowing you will come back for more soon. Alongside the already existing drug epidemic in Punjab, reliance on the state is another drug, and we are all addicted.

Lastly on this point, the government is only able to guarantee a minimum price by buying up all the excess produce. Forgetting for the moment that tonnes of this never goes on to sell to end consumers and rots in warehouses [7], they can only do so with taxpayers money! [8] The citizenry therefore, pays twice for their food. Once through buying it from markets, and secondly through taxes.

Getting our definitions right

Before solving a problem, you need to be able to accurately define the problem. India is not a free-market in the slightest. Despite what you may have heard from different commentators on the Morcha when it was in full swing, none of this was due to capitalism. In fact, it was precisely due to the lack of free-market capitalism and Nehru’s adoption of socialist methodology after India’s inception in 1947. The Soviet-inspired central planning and government interference in the economy has led to this, and continues to disrupt the Indian economy [1].

Many of you reading this may be put off by me saying this, but the truth is that the narrative surrounding these terms have been hijacked by the political left (don’t get angry too quick that I may have called out your team, the right is no better either). So let’s define terms and make this really clear [2]:

Capitalism:

an economic and political system in which a country's trade and industry are controlled by private owners for profit, rather than by the state.

Free-market:

an economic system in which prices are determined by unrestricted competition between privately owned businesses.

And while we are at it, lets also be clear about what the difference between the public and private sectors are too:

Public Sector:

the part of an economy that is controlled by the state.

Private Sector:

the part of the national economy that is not under direct state control.

So when we were hearing about the ‘evils of the private sector’ and the ‘greedy capitalist exploitation’, what we were actually hearing were the ravings of people who had no idea what they were talking about.

The farmers themselves are classed as the private sector by definition! You know who isn’t the private sector? The state-backed monopolies of Ambani and Adani who absolved any right of being classed as private by colluding with the government.

These state-backed monopolies are not capitalist or free-market entities in the slightest. By establishing a link with the state (public sector) they absolve any private status they had. If it is not private, then it isn’t capitalist or free market — by definition!

If anything, it’s (state) socialist [4] or (state) communistic:

Socialism:

a political and economic theory of social organization which advocates that the means of production, distribution, and exchange should be owned or regulated by the community as a whole.

Communism:

a theory or system of social organization in which all property is owned by the community and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs.

Marxist Communism is literally the relinquishing of all private sector ownership of the goods and services to hand over to the state. And before the socialist types come to complain about this; NO, placing the “community” above the rights of each individual and having that political community led by a group of representatives falls under the definition of a state.

Although historically socialism has always been a collectivist, pro-state, pro-central planning ideology, the modern left have co-opted this term and instead claim the “community” would have control rather than the state. But if that community is represented by a government that decides on each individual’s behalf, this is exactly what a state is.

State:

a nation or territory considered as an organized political community under one government.

And if you don’t like these definitions, Karl Marx makes his anti-private, pro-state, pro-central planning stance very clear in his ‘Communist Manifesto’, especially his ‘10 Planks’ to achieve communism [5].

However if you are willing to reject the idea of a state/community run by one government or any body of representatives deciding on the behalf of individuals in their group and taking control of resource management, then you are what I class as a non-state socialist. An often confused and self-contradictory position, however tolerable if the claimant of this stance indeed adheres to this type of socialism.

In this case the ‘community’ in your view would just be made up of private individuals, interacting and exchanging with each other voluntarily. No one person having to give up their rights to appease the collective. And that’s a fundamentally capitalist position so can easily co-exist under a wider free-market framework [6]. To distinguish between the two types, ask a self-proclaimed socialist whether they would like to privatise industries or nationalise them.

And whilst we are on the topic, it is also necessary to address the following myths too. Colonialism and the British Raj were not capitalistic either. They were state efforts (public sector), not private sector efforts. The East India Company was a state-backed monopoly [7], similar to how Ambani and Adani are today. Corporatism is not capitalism either, since as soon as large interest groups gain control over the state they are no longer private [8].

I can’t speak to how well the communists present in the Morcha knew about their own ideology, but the ideology itself they promote, if implemented at a state level, would have been a disaster. It would have solved nothing, as any sort of communist takeover would have just replaced the current state with another form of state. In all likelihood, given the communist/socialist experiments in the past, it would have been even worse than the current government is now.

By demonising terms like private sector, profit, capitalism and free-markets etc. actual effective ideas (if implemented correctly) are being thrown out and replaced with broken ideas disguised in different ways to keep the people subjugated by broken systems of corruption and over-reliance on the state. Our adversity for certain terminology is redirected our trajectory from liberation to further oppression. As a result, we are literally begging the state to solve the problems it itself created through the very mechanism of state intervention that caused these issues in the first place!

This is why getting our definitions clear is so important, since when most people hear words like ‘private sector’, instantly imagery of obese, greedy businessmen come to mind. It’s such a clever tactic politicians use when they blame the private sector (you and I) for the problems they create. And as a solution, they curb our freedoms and create more perverse incentives.

As more libertarian philosophy, Azadism considers the left-right wing dichotomy a nonsensical distraction designed to keep a population bickering amongst itself. Through this, the real battle is obscured — the struggle between liberty and authoritarianism.

Libertarianism:

a political philosophy that advocates only minimal state intervention in the free market and the private lives of citizens.

Both sides of the political spectrum are full of hypocrisy for this reason, since they ignore where freedom is hindered in order to serve the interest of their side.

It’s especially disappointing to see amongst my fellow younger generation Sikhs who have become ‘shills’ of the left. So much so, full-blown communists permeated the Morcha without many people stopping to think about the shear ridiculousness of this. It was the principles of communist ideology in state-intervention, central planning and anti-free-market sentiments that caused this whole situation to arise in the first place! [9]

The Three Bills

A quick summary of them given what we learned so far.

1. Farmers' Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020

2. Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, 2020

3. Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act 2020

I won’t repeat what is said in them here, and so you are encouraged to read them yourselves if you have not already [1]. Instead I will briefly comment on each one.

The first bill is just opening up options for farmers, and can hardly be an issue to complain about. In fact, much of this opportunity to trade outside of government mandis already exists. The resistance was instead directed towards the idea of getting rid of these mandis altogether. Whilst this bill makes no mention of abolishing it, it does set the ground for a future removal of that system. The farmers concerns here a definitely valid even if this wasn’t explicitly mentioned, since the rapid introduction of these bills in general, without warning perhaps didn’t inspire any confidence that an approach to phase out the relied upon mandi system would be any different in terms of pace.

The second act aimed to introduce a national framework for agricultural contracts including a three-level dispute mechanism. On the surface, this also sounds reasonable however given the states track record in matters of justice, caution must be taken to any solution including their involvement. Given also the fact the states independence on these issues are compromised via corporate political activity, any unbiased judicial process involving the state seems far-fetched.

The third act removes state imposed restrictions on the stock piling of certain crops and grains. However, if the prices rises over 100% or 50% for non-perishables, then stock limits can be reimposed. There is some disagreement about the level of price increases being too high for this to be relevant at all. However, in terms of economics the worst way to solve an increase in prices is to artificially restrict the supply further or confiscate stocks for manual distribution as this would only disincentivise the further production required to bring prices back down naturally.

If the fear is that by removing stocking limits, companies would just restrict the supply themselves and cause the prices to rise, this fails to consider some crucial factors. Those companies would have to forgo income from selling their stock and bet on prices rising in the future high enough to offset the costs of storage. If there are only a few companies that are allowed to stockpile, then this would indeed be a valid concern. However, if the right for anyone to stock grains or produce is assured (including the farmers themselves), then this risk is drastically reduced since the supply would not be constricted into so few entities. If one hoarder is restricting their supply, people would just go to someone else. They cannot forcibly restrict the supply of others in a cartel-like structure when there is ample opportunity for competition to come in and offer these resources instead. Instead of a few firms to collude with, they would have to convince thousands to comply with their strategy for it to work (including the farmers themselves).

Although largely overlooked in the discourse around this bill in particular, the clause around regulation of the food supply in “extraordinary circumstances (such as war and famine)” is also worthy of scrutiny. As the saying goes, “if you let the state break the law in an emergency, they will create an emergency to break the law”.

Now initially, anyone with even a basic understanding of economics would notice that these are actually quite positive and aim to remove state intervention and promote economic freedom for farmers. And this is true; that is indeed what these laws would do IF India was in the correct position to adopt them. However as discussed above, India is not ready for these sorts of policies to come into effect just yet. Much needs to be done before getting to this condition. For example, if the state is removing barriers for farmers to transact freely in the private sector, this is in principle great. However, if that “private” sector is dominated by state-backed monopolies, then this reform is superficial. It is merely the state changing its clothes. It can’t even be called privatisation since as discussed previously, the private entities lose their private status when they collude with the state to stifle the free-market competition these bills claim to promote.

However, with that said many of these proposed ‘reforms’ already were in effect and should have been guaranteed by the law anyway. Likewise, we shouldn’t be blinded to some of the positive aspects proposed in these either (for instance, the removal of excess state fees outside of designated trade areas). A balanced view must be taken if we are to accurately assess potential solutions.

On one hand, the protesting farmers have legitimate concerns about this, and on the other hand the implementation of free-market reforms may indeed lead to positive change in the long-term, even if the short term is rough. However, the short-term will only be abrasive if the government pushes in reforms at the wrong pace, and without the correct pre-conditions. Implementing some of these things and opening up a state-reliant agriculture industry to the so-called ‘private’ sector overnight in the current state of India would likely by a disaster for many in the short term, and it is preventable if only a more Azadist approach is taken to gradually phase in economic freedom over time.

The Azadist Approach

How could Azadism be applied here?

To start with, let’s first give the definition of Azadism:

Azadism:

an economic and political system that encourages limiting the role of government to upholding the Non-Aggression Principle and preserving property rights. This takes the form of four main roles, namely: National Defence, Policing, Justice System and Tax Administration. The control over a nation’s economy is gradually transferred away from state control and to the people directly, where both parts are adequately independent of each other. Initially administered under a decentralised Khalsa confederacy of Misls, over time the role of the government can be further reduced and replaced entirely by the private sector.

The full ideology is outlined in the Azadist Manifesto [1].

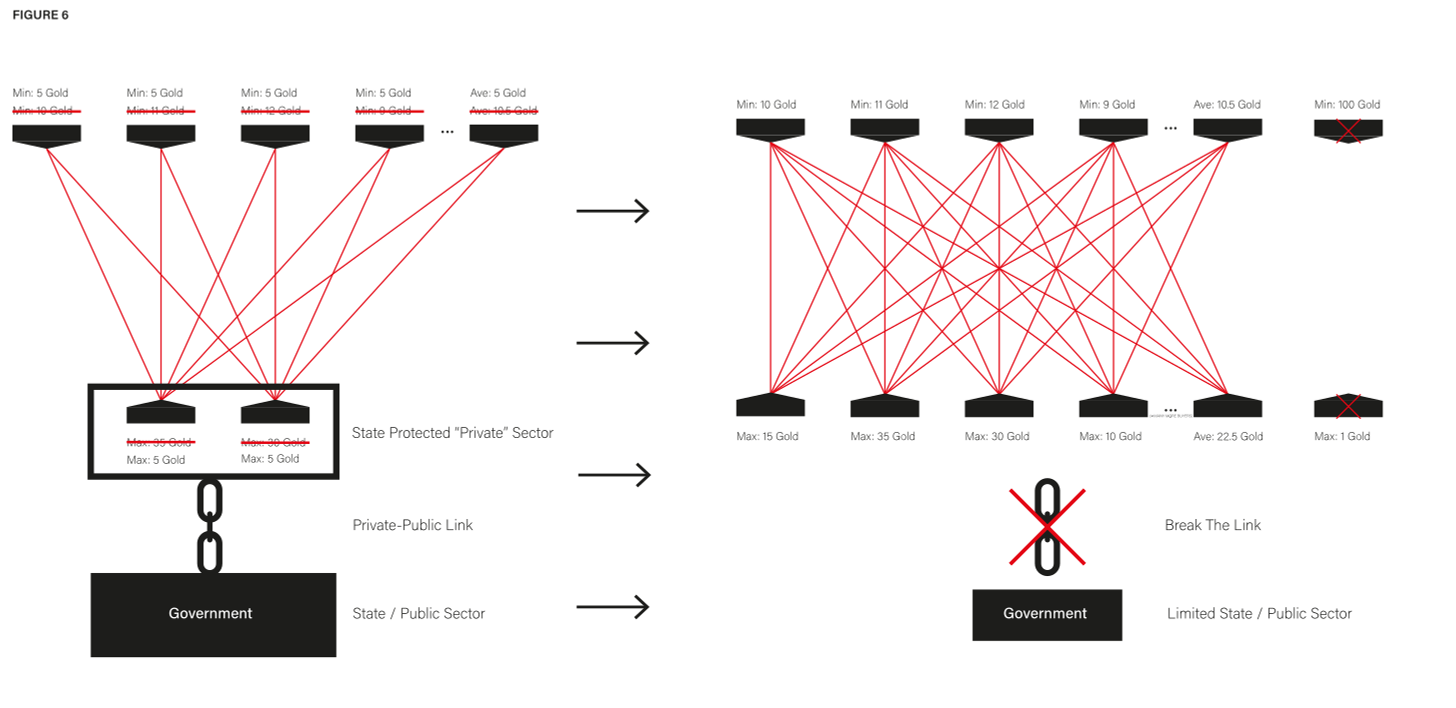

The Azadist approach would prioritise breaking that link between the public and private sector entirely. Amendments would need to made to constitutionally outlaw lobbying and corporate political activity with harsh punishments for anyone who violates this. This would truly set the standard in removing barriers to entry and inhibits the ability for firms to use the government apparatus as a tool to stifle free and fair market competition.

At the same time a basic income scheme would be implemented, replacing the reliance on a minimum price to provide living wages. Azadism currently favours a Negative Income Tax (NIT) approach to this where all those earning beneath a certain threshold amount (likely the median income) would be subject to a negative income tax rate [2]. This wouldn’t replace MSP straight away, instead it would be offered as an alternative to begin with, state by state. Since this is paid for regardless of output or employment, the pressure is lifted off the farmers from producing specific crops. Instead, now the laws of supply and demand can actually work as farmers are freer to comfortably experiment with production to actually meet the consumer demand since their living wage is not so dependent on what they grow.

This could also help re-establish incentives away from monoculture farming techniques of unsustainable crops using ridiculous amounts of cancer-causing pesticides. Instead, more sustainable techniques like polyculture farming [3] can become more accessible. As well as this, the farmers would be in a far safer position to invest in newer technologies such as those that use less water like hydroponics or vertical farming methods.

Reasonable concern can be raised that farmers can’t adapt to demand as quick, it takes months to grow crops. Hence why these measures should help incentivise farmers to stop growing so much of the same crops for acres and acres. Instead, perhaps this way they will realise a greater benefit in scaling down and diversifying their risk with polyculture farming techniques. Many different crop types can be grown to test the market. Over time, a sense of the demand may re-establish as the farmers get used to a system where the government doesn’t just buy whatever crops they incentivise them to grow, regardless if the people actually need it.

Secondly, by diversifying like this, the crop-income security goes both ways. If they grow a crop that is in demand but not everyone grew it, they would now be able to charge a higher price for it (limited supply + high demand = raise the price). This would also help offset any produce that had a dip in demand that season.

Alternatively, income security can also be achieved through accurate and solid contracts with buyers. However, it is up to them to understand the terms written in it and clearly outline what is being exchanged. There is not a need for government to step in here and potentially bias legal disputes in favour of one party over another. Contracts can be drawn up by dedicated private lawyers and third-parties whose income does not depend on taxpayers money, but their market reputations as fair and reliable arbitrators and contact designers. This way they must work hard to uphold their reputation lest they lose their source of income and potentially face legal repercussions for fraud. In fact, with the advent of blockchain technology and smart contract capabilities, there may not even need to be a need of a third party at all. Hence why also, as part of the Azadist strategy, all restrictions related to cryptocurrency and blockchain related projects should be lifted in India so to attract entrepreneurs of this technology into the nation and provide these solutions [4].

To further curb the power of large corporations and make it harder for monopolisation is to lift barriers of entry into industry. Monopolies are the opposite to competition by their nature [5]. Therefore, we need more competition, not less, which would put pressure on these large corporations. By removing their ability to legally lobby, this will already do much to cripple their power, but other policies may include reducing tariffs. As a result Indian goods/services would become more financially attractive and this will further allow for greater access to global markets, thereby adding players to compete with the large domestic firms. At the same time farmers would experience an increase in demand for their produce as they would have easier access to a greater customer base. You would expect many organisations arising to export, not just crops but many other goods and services. International trade become easier once tariffs are removed entirely, increasing demand for Indian crops globally. Indian agriculture becomes more competitive, as well as making it cheaper for farmers to sell to clients abroad. Knowing that farmers have viable alternatives through foreign buyers, it would also help incentivise domestic firms to offer fairer deals.

We need to abandon this “Made in India” propaganda spouted by the state as its only real purpose being to protect large Indian firms from international competition and investment, which could outcompete them on price, quality and working conditions. Protectionist policies only protect the large corporations at the expense of the poor and working class. They have reduced access to goods/services and the opportunity to work in conditions that are more favourable with better reimbursement. When new entrants enter the market, it forces existing firms to increase affordability and quality, as well as working conditions for its employees in order to stay competitive. If the old organisations can’t balance this as well as others, consumers and employees would both go elsewhere. One of the primary reasons why they usually cannot currently is because there are so few other choices competing for their labour [6]. Through these policies of increasing competition, choices and alternatives arise. This is what the people need the most - more and better choices.

And perhaps the most important of these new choices would be opportunity. By having a more cost-effective economy, instead of Punjabis emigrating abroad for work, the companies and opportunities would come to them. Over time this would also provide some much needed development in Punjab as foreign investment increases. But maybe more critically, this would help diversify the Punjabi work demographics altogether. Instead of such a large proportion of our community being farmers and working in the same industry, we would be able to move into many new industries.

We can’t have it both ways. If everyone's a farmer, then there is an oversaturation of labour supply in this sector. This means that the income available for the agricultural industry is spread over a lot more people, and each has far less bargaining power. You can’t preserve farmer traditions for nostalgia’s sake whilst also wanting to become wealthy, high income earners. There has to come a point where we have to let more efficient and effective processes take over. People must gain new, more up to date skills. We must progress from old ways of doing things so that we can innovate with new methods that can drive down costs and prices, as well as increase purchasing power for both consumers and producers. The current situation is not sustainable. How many times can each farmer split the land they own amongst their children? This is an inherent bottleneck with the way this sector is operating, and farmers will be increasingly owning smaller plots of land.

Even then, if the desire is still to farm and preserve traditions then consider this: what is so traditional about pumping your soil with cancerous chemicals and growing unsustainable crops that are destined for under-consumption, whilst drowning ourselves in debt? If people still want to farm and preserve this activity then they could do so organically on a smaller scale in the comfort of the leisure time afforded to them through careers in less physically demanding roles. This is all being actively hampered by our own attitudes and government intervention perpetuating a poverty ridden agricultural sector stuck in the past and restricted from innovating through the perverse incentive structures they have established. There is risk to change, but there is also risk to staying in the same broken system. That risk is being realised today with the high rates of cancer, suicide, debt, low income and escapism to the west [7].

We need to explore new industries and new career paths. Diversify the community economically. We have all our eggs in one basket of farming, and so whenever anything happens it is a big shock to the whole community. Especially in the Indian system, as it makes the community extremely reliant on the state for their income. Security of food, shelter, for their very survival has been handed over to the state to an obscene level. This is not very strategic at all.

Alongside this, to further increase competition, choices and opportunity, Azadism would reform the tax system by simplifying and limiting it. The Azadist Manifesto delves into more detail about this subject [8], however for now the strategy would be to remove all corporation tax (alongside other types), leaving just one type of tax (income, consumption or land revenue are some options). This will further reduce the barriers of entry into business as the cost to set one up and maintain it are drastically reduced, making it easier for anyone to start and run one. This would also help farmers diversify into other industries much easier, as not only would alternative opportunities arise, the cost to be self-employed with their own business is reduced.

This helps ensure that competition is healthy and perpetual, constantly motivating each business to provide a good or service at price and quality people are willing to pay for. At the same time also balancing the working conditions and benefits for any employees, lest they choose to go elsewhere seeking a better deal.

You may be thinking, that if you so drastically remove tax streams to the government it’s collected revenues would drop. Good. This will force the government to cut back on unnecessary spending and divert efforts on providing the necessary conditions for a free market to function. Secondly, many government schemes and programmes would be removed in place of the NIT system, thereby avoiding further inefficient and costly state programs.

Additionally, an Azadist conception of government is a limited one anyway, restricted to only a few functions. The state needs to only be a referee in the market, not a participant. It should refocus its efforts on law, justice and national defence. Plenty to keep them busy with. With more energy devoted to these, the corruption can come under refreshed and increased scrutiny. And this part is essential. Much of this relies on a justice system that’s functional and absent of widespread corruption. Disputes need to settled in courts of law that can be trusted and relied upon, and criminals who break the law must be punished. The state needs to also make itself more transparent for private regulators to come and assess quality and assurance of judicial practices, lawyers, judges etc. Since these will be independent, private-sector regulators, with an incentive to find flaws [9], more corruption is likely to be called out and the people can easier and more specifically demand alterations and punishments for the corrupt.

It is crucial for any policies to work that we first reform the justice system so that trust can develop in them and they can be relied upon to adjudicate legal matters fairly [10]. This is what we should have been protesting for. Another highlight of our community’s inability to save ourselves is our lack of negotiation skills. Whilst it may have seemed a success that the laws were repealed (as they should have been), a more strategic outcome would have been a deal.

Essentially, given the above economics of these bills, we should have instead said to the government that if you implement the kinds of reforms mentioned in this publication first, only then will we accept these laws. Now although much of the opportunity to present this has now gone, it is still not out of the question. The ability to mobilise and shut off the capital city is still fresh in their minds, and the ruling administration would not want to go through that again. We should leverage this and use it as a bargaining tool to re-initiate negotiations. The system we have gone back to is just a slower death. Let’s make the necessary changes now before it is too late.

9 Measures

What would be the Azadism-based demands?

1

First, the government should provide a non-commodity related safety net through the NIT. This should be a replacement to existing programs and government schemes, not an addition to them. The aim is reduce reliance, not increase it by letting the state decide how they should spend their money.

2

Second, the link between the public and private sectors must be broken, a relationship that poisons both parties at the people’s expense.

3

Third, the government needs to stop creating perverse incentives through price manipulation.

4

Forth, harsh punishments should be handed out to those who are caught lobbying (now legally considered bribery) or using corporate political activity to gain favours from the state. So harsh should be these punishments that the first convicts should act as an active deterrent for this behaviour. But by also curbing the power of state to influence the economy, the incentive to use them as a tool for your own gain diminishes anyway.

5

Fifth, a real justice system reform needs to take place, perhaps taking lessons from other nations, so that confidence can be held in the judicial process and that criminals who break the law will be punished.

6

Sixth, through leveraging blockchain technology, smart contracts could be employed to help facilitate clear and fair contracts without the need for potentially biased third parties. Any artificial restrictions set by government in this sector should be removed.

7

Seventh, the people themselves, including NRIs and OCIs should make a private effort to invest back in their homeland, showing real monetary support for Indians by contributing to the economy and creating new industries. Invest not just money, but also knowledge. Experienced professionals who are nearing retirement should be going back to Punjab to teach what they learnt in the west. Wherever possible, hire talent in Punjab, especially roles related to IT which can be done remotely. If you are working and becoming stable, don’t get married and then move out of your parents house. Transfer ownership of the property to you, and send them back to Punjab [1].

8

Eighth, Punjabis should seek to educate themselves in skills people are willing to pay for. This many farmers are not needed, and having so much of the population reliant on one sector is a recipe for disaster. Diversify, and those who are left should be encouraged to use more efficient technology and farming techniques that removes the need for so much labour and effort. These things will naturally arise when the government gets out of people’s way and allows the sectors to innovate themselves. The only support the state needs to provide is maintaining a free and fair market via a functioning justice and defence system and a safety net in the form of basic income only. No state programs are needed, especially when they are so prone to corruption and inefficiency. These should be our demands.

9

Ninth, denationalisation and removal of state intervention in the financial system. Central Banks manipulating interest rates and creating artificial inflation is the source of many of the issues in economies around the world. Whilst this publication will not detail this further, a later write-up on this topic may be explored in more detail in future. However, the effects of this measure would be increasing private competition in the banking sector so that fairer interest rates, based on market forces can be offered on loans and deposits. Access to financial services such as investments would also be beneficial for low income earners to help grow their wealth. Alongside banking, insurance industry would also be promoted via a more fair and competitive system. This way farmers could more easily apply for crop insurance at better rates. Even individuals across the world can choose to take on the risk and invest in farmers by offering these insurances in return for a fixed monthly payment.

Once these things start coming into effect, the removal of the state mandi system can begin. The solution here isn’t more government intervention, it’s less. The governments are merely servants of the people, not the other way around. By adopting an Azadist approach we can shift the balance of power into the hands of the people and remind them of their rightful place.

Final Note

This essay does not intend to be an all-encompassing overview of the Indian agriculture industry, and there are other aspects worth more study. This was just an analysis of the economics of the situation from an Azadist perspective. Much of this I felt was either overlooked or misunderstood by our Panth especially. Hence, misinformation and manipulation spread easily. Socialist and Communist ideologies gained a foothold by taking advantage of the situation to place the blame on free-markets and capitalism, however after drilling into the details this couldn’t be further from the truth. That ‘public-private’ sector link that the Azadist approach aims to break, is exactly what these Marxist ideologies are. They blur the lines between the state and the private sector, so that the corrupt and authoritarian elites can take power.

Those of you who are too entrenched in your leftist or right-wing political ideologies may not like what I have written here, and that’s okay. My aim is not to convince you, its to help educate those who are genuine about learning and want to see real change in this world along the lines of Gursikhi and Khalsa values. Many of these stubborn types, seeing their ‘team’ being rinsed here and their worldviews challenged probably wouldn’t have even read this whole thing.

As always, debate and disagreement is encouraged and I am happy to hear it. If you would like to write an essay or article for Bunga Azaadi either on this topic, or anything related to Sikhi, statecraft and economics (and more), please get in touch. My aim isn’t to make the whole Panth conform to my way of thinking, only to ask those of you who want a more strategic, proactive long-term approach to our Azaadi to step forward and make yourselves known.

Bunga Azaadi — Institute for Azadist Studies

Follow us on Instagram

For email updates, sign up to our Substack

Want to support? Support (azadism.co.uk)

Questions, suggestions or disagreements? Get in touch!

email: contact@azadism.co.uk